|

|

A Lone Woman In Ireland.,

Page 7 of 13  The Geologists

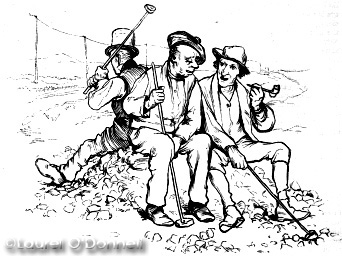

“I must get my family and luggage to the nearest inn,” my friend returned; “and as there is no other means, I certainly accept such as I am offered.” On the arrival of the party at their destination my friend proceeded to pay the price demanded, when the Englishman rushed up in horror, and cried out that they had been outrageously imposed upon, as they had paid the gillie four times as much. “Ah, weel, mon,” said the old Scotchman, with inexpressible gravity, “ye wad make your bargain, and ye hae your bargain; but this gentleman trusted to my honor, and I only asked him the usual fare.” The sun, softened by the humid air of this mild climate, where the wind seems tempered for the shorn lamb, shone with peculiar richness on the morning of our departure from Galway. For a few miles the road lay over a gently undulating country, beautifully shaded by overhanging trees, which retain so long their rich green. It was market-day, and the peasantry and small farmers, with their wives and children, were wending their way to the city with pigs, sheep, turf, and flannel. As I watched them with their bright garments, now dotting some sunny expanse, now disappearing in the shade of the trees, I thought their light steps seemed less laden with the weight of care than those of any mortals I had ever seen. After proceeding a while in this embowered road, where the solemn twilight was only broken by occasional gleams of the mid-day sun, we were startled by the shrill yet plaintive notes of the Irish bagpipe. By a spring which made a spot of way-side refreshment for the country people, was a humble cottage, whitewashed to a dazzling brilliancy, and by its door sat an old man, who played upon the pipes. While Flanigan regaled his pony, and lamented the absence of poteen for himself, I sketched the musician. “It is seldom,” said Flanigan, remarking upon the gratuity I had given in return for our entertainment, “that he sees the color of coin; a potato or a piece of turf is all that he gets for his music, for the real travelers who bring money into the country and spend it, they are rare. Few one sees on these roads who are not natives, except the anglers going to the lakes, or them geologist men who go about the country cracking stones, like the poor divils ye see at the way-side, except that no road seems any the better for their labor.” A little further on we passed the wild and lonely Ross Lake, and the country now changed to mountains and moorlands. Cottages became more rare, and cultivated fields were followed by dreary stony moors. Flanigan, who professed to know every thing, insisted upon our turning off to see Lough Corrib, where, he said, there was a ruined castle that had belonged to the O’Flahertys; and as, following his suggestion, we left the main road, my attention was arrested by a graveyard of sadder aspect than any I had ever seen. The graves were huddled together without order and overgrown with weeds, and the unhewn stones which marked them, probably gathered from the neighboring fields, bore neither name nor date; yet sad as was this crowd of unrecorded dead, I asked myself whether it were not better, after all, that their epitaphs should be graven upon the hearts of those who loved them rather than upon the head-stones that have become symbols of falsity. |

|

7

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|