|

|

Chapter VIII.

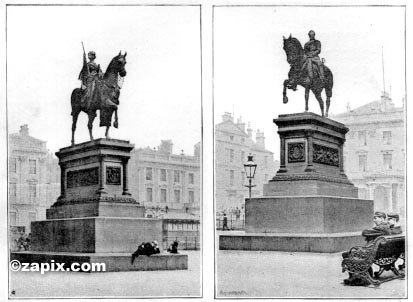

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert  Queen Victoria (Left); Statue by Marochetti. Erected in St. Vincent Place, 31st August 1854. Removed to the Square, 2nd March 1865. Prince Albert (Right); Statue by Marochetti. Erected 18th October 1866. At three o’clock on a midsummer morning, the l0th June, 1837, the tolling of the great bell of St. Paul’s floated in waves of solemn sound over the length and breadth of London. Its solemn booming was heard, too, far away in the green fields and hop gardens of Surrey and Kent, in which many of the labourers were already astir. By-and-bye the bells of other towns and cities far and near, including our own, were rung out in slow, solemn tones. The natural question arose on every tongue, For whom was the knell rung out? and the answer came, “King William is dead!” So was broken the news over all the land. Our city records tell us that the official announcement was read aloud to great crowds of our merchants and citizens that had assembled both in the Royal Exchange and in the Tontine Reading Room. The Tontine was the Rialto, or temple of commerce, of Glasgow until the Royal Exchange was built in 1825, and for many years subsequent to that date shared honours with the latter building as a place of business resort for the city’s cotton and tobacco lords, and other merchants. For some hours previous there had been anxious watching and soft whisperings in that darkened chamber in Windsor Castle. Death came at the stroke of two, and King William IV., just at the dawn of Midsummer Day, fell on his last, long sleep. The Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Lord Chamberlain, the Marquis of Conyngham, who had been summoned to Windsor when there was no hope for the King, hastened to Kensington Palace to acquaint the young Princess Victoria of the event which now made her Queen of the British dominions. The distance was 21 miles, but the distinguished messengers were borne by the fleetest of horses, and at five o’clock in the morning Kensington was reached. A court pen has described the incident with a picturesque and winsome simplicity as to how our Queen received the tidings: “When the messengers reached Kensington Palace, occupied by the Princess Victoria and her mother, the Duchess of Kent, they knocked, they rung, they thumped for a considerable time before they could rouse the porter at the gate; they were again kept waiting in the courtyard, and then turned into one of the lower rooms, where they seemed to be forgotten by everybody. They rang the bell, and desired that the attendant of the Princess Victoria might be sent to inform Her Royal Highness that they wished an audience on business of importance. After another delay and another ringing to enquire the cause, the attendant was summoned, who stated that the Princess was in such a sweet sleep that she could not venture to disturb her. Then they said, ‘We are come on business of state to the Queen, and even her sleep must give way to that.’ It did give way; and, to prove that she did not keep them waiting, she came into the room in a loose white morning gown and shawl, her night cap thrown off, and her hair falling upon her shoulders, her feet in slippers, tears in her eyes, but perfectly composed and dignified.” When informed that she was now to be Queen of Great Britain, she immediately and instinctively said, “I will be good,” and asked the venerable Archbishop to pray for her and for the kingdom. The Queen’s right of succession in the royal line lay in the fact that King William IV., third son of George III., left no heir to the throne, and that she was the daughter of the Duke of Kent, his brother, fourth son of the same monarch. |

|

26

:: Previous Page :: Next Page ::

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|