|

|

Yuletide In An Old English City,

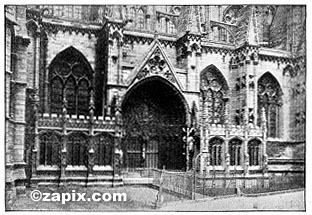

Page 5 of 8  The Choir, Lincoln Cathedral

monument, desolate and forlorn, against which the cattle rub their horns and browse in comfortable indifference. What a strange procession that would be, which should include a few individuals from the successive centuries, out of the concourse that old archway has frowned upon, — what strange jargon in the gradual formation of our language, what costumes, what habits Few of the citizens take note of that weather-beaten relic, but Lincoln would not be what she is without it, for it is one of the few monuments of her old-time greatness.

The first words to attract our attention as we enter the city are those of two neighbors greeting each other on the doorsteps of their cottages with questions bearing on the all-important Christmas plum pudding, and the mournful declaration of one that hers ought to have been made a month earlier. Suddenly the sun bursts forth, and there on the brow of the hill just before us the stupendous cathedral, high over all, like some monarch, erect, immovable, shoots its three massive towers into the sky, revealing its fine proportions in the morning light, which sparkles on the windows and weathercocks, and throws out sombre shadows from its buttresses. To narrate the incidents of national importance connected with the history of Lincoln would be a task from which any student might well shrink. In this ancient city is wrapt up a great part of the history of England from earliest times. Roman columns, tessellated pavements, and rare coins, some recently unearthed, bespeak its antiquity. Dark, ominous, and threatening, the old Norman castle on the west side of the cathedral, once a royal demesne, with its embattled walls, its keep, and its Lucy tower, where more than one royal prisoner was detained, marks the scene of many a bloody conflict during the reigns of Stephen and John. Among the walls crop up quaint hood-mouldings and corbels, mullioned windows, old archways filled with wrinkled oaken doors, grotesque heads of kings and devils extruded from mouldering eaves, the whole covered with ivy and cypress-trees, and partly surrounded on the south and west, facing the town below, with tall poplars and pines thickly studded along the embankment, in which the antiquated crows build their nests and rear their young. Up that steep, narrow hill, on which old-fashioned dwellings lean, like palsied people huddled together for warmth, we fancy we see the pilgrims, at least seven centuries ago, dressed in the self-same costumes described in the "Canterbury Tales," wending their way to the shrine of St. Hugh in the minster; while a glance to the east shows us the ruins of the old palace in which King Henry VIII quarrelled with a cardinal on the legality of divorce. On the opposite hill, Cromwell, with his broad, red face, held the citizens in terror for several days, while in pursuit of the rebel army, tying up his horses in the nave of the minster. The city is divided into two parts, — above and below hill. The upper part is the retired, aristocratic neighborhood, looking not so much remote from the world as limping behind it, and wearing a proud and haughty air as if it cordially despised the bustle and fret below. As we glance downwards from the summit of the hill, we are surprised at the innumerable tall chimneys, and understand that the clanking and hammering, sometimes not unlike the sound of distant |

|

5

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|