|

|

On The Welsh Border.,

Page 14 of 14 heart of every pleasant belief, and tear that heart deliberately out, under pretense that they are getting at the truth. A murrain on the truth, when it dares to tell an unhappy world there was no William Tell, that Joan of Arc died in her bed an old woman, that Charlotte Corday was not handsome nor, pure, and that Benedict Arnold led a comfortable and contented life in a foreign land after he had betrayed his own!

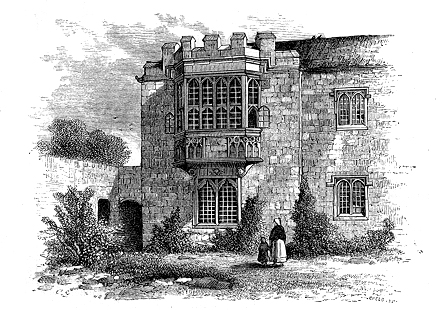

Geoffrey’s Window.

The feature of all others most interesting in Monmouth is the window which lights the room in which that delightful old Geoffrey spun his fairy web of history made wonderful. It is a great stone hanging window of quaint and curious aspect, mid dark with the grime of centuries, and it is renowned throughout the land as Geoffrey’s Window. Geoffrey was a Benedictine monk, whose surname was Ap Arthur, and who was archdeacon of Monmouth in 1151. It is a momentous reflection, as you look up at this window, that you here stand at the head waters of that glorious stream of historical fiction which has rolled its musical tide down the centuries, telling over and over with perennial delight the tales of Arthur and of Merlin. Had not Geoffrey of Monmouth written, there would have been no “Idyls of the King,” the life of King Arthur would have come down to us barren of that wealth of story which now makes it peerless in the realm of romantic tradition. It was this Welsh priest who seized upon the faint records of an age which was ancient even to him. but to which he was nearer by three centuries than Caxton, who printed the Morte Darthur some 350 years before Tennyson’s time. It was Geoffrey who made immortal the Arthurian romances embodied in the old Breton lays sung by the twelfth century harpers, and who wrote the life of the Welsh prophet Merlin. The country surrounding Monmouth is no less rich in interest than the town. The author of the “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” was here in 1770, and writing of the Wye, said: “Monmouth, a town I never heard mentioned, lies on the same river in a vale that is the delight of my eyes, and the very seat of pleasure.” The town stands in a lovely valley surrounded by mountains whose very summits are cultivated like parks. On one of these heights there is a Roman camp within the spacious grounds surrounding the mansion of a private gentleman. From this camp half a dozen other military posts are visible, some near by, and others at distances of twenty miles off. According to traditions which we eagerly credit, and which the coldest judgment finds good reason to approve, the heroic Caractaeus often occupied this camp during his nine years’ struggle against the Roman invaders; and from its summit he could see the trees surrounding his clay-built home — at once a hut and a palace — in old Caerleon. The lofty height afforded him a secure retreat, with his half-naked and poorly weaponed warriors, when the mail-clad and well-armed Romans pressed them too hard; and it was no doubt owing to the opportunities for recuperation afforded by these mountain fastnesses that the sturdy Cambrian king was so long able to make war against an enemy so vastly his superior in numbers. |

|

14

—End— Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|