|

|

On The Welsh Border.,

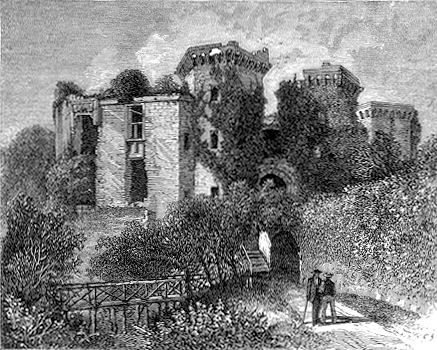

Page 12 of 14  In The Moat, Raglan Castle.

Richard Strongbow, in the twelfth century, gave the domain and castle of Raglan to Sir Walter Bloet, in consideration of soldiers, money, and arms furnished by Bloet for Strongbow’s expedition into Ireland. The story of most of Raglan’s lords is a story of bloodshed and death by violence. Sir William ap Thomas, who owned the castle in Henry V.’s time, had two lusty sons, one of whom was that gigantic knight, Sir William Herbert, whose monument we have seen in Abergavenny Church, and who did such prodigious slaughter with his poleaxe at Banbury battle. The other son, who dwelt here under Henry VI., also espoused the cause of Edward IV., and also lost his head at Banbury. The next inheritor of Raglan was made justice of Smith Wales by Richard III.; and the next, who got Raglan through marriage, was beheaded at Hexham. And so these old knights went on fighting, marrying, and being beheaded, with tiresome frequency, until the day of the Earl Edward, Master of the Horse under King James I., who “died rich, and in peaceful old age — a fate that befell not many of the rest; for they expired like lights blown out, not commendably extinguished, but with the snuff very offensive to the standers-by.” Then came the reign in Raglan of the noble Marquis of Worcester, which period surpasses in interest all the preceding centuries of this stronghold’s history rolled together; for not only is it the record of long and hard fighting throughout the Cromwellian wars, but it includes the story of the invention of the steam-engine by the son of Raglan’s lord. The fame of the water-works of Raglan in the seventeenth century was spread throughout the kingdom. Not only were there wondrous great fountains on the bowling-green and in the fountain court, where stood a statue of a white horse and other figures, from which spurted fantastic streams of water, but in the moat there were amazing engines which threw a glittering spray clear to the top of the eat donjon keep. At all fetes within the castle walls these water-works were set in motion, to the delight and wonder of the knights and ladies, who looked on them as the vision of some fairy tale. It is night when we enter Monmouth, a town renowned in history, but more renowned on account of its historian, Geoffrey of Monmouth, perhaps the most delightful old liar who ever wove historical lore out of his inner consciousness. Henry V. was also born in this town, but Henry of Monmouth, by that name, is less famed over the world than Geoffrey of Monmouth. That quaint old chronicler, Speed, in 1610, in his Historie of the Kingdom, wrote thus of Monmouth Castle: “But as all things find their fatall periods, neither may any more |

|

12

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|