|

|

On The Welsh Border.,

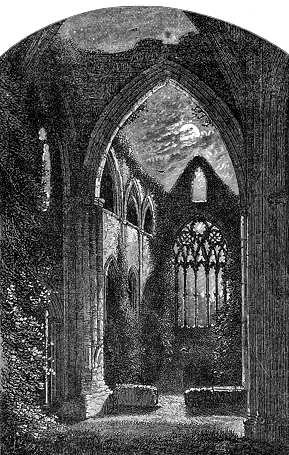

Page 10 of 14  West Window, Tintern Abbey.

of Roger de Bigod, Earl of Norfolk, who built the church — a strange, ghastly, broken figure, of gigantic proportions, with its head and members lopped off, as if it had been put through some hitherto undreamed-of refinement of inquisitorial torture, in which it had been literally broken all to pieces. It came to this lamentable state, however, through the freak of a drunken Welsh sailor, who, passing this way in the course of a spree he was occupied in conducting, mistook the effigy for a person on pugilistic purposes intent, and so proceeded to knock its head off its shoulders. It is needless to say this was a great many years ago, when the ruin was open to the incursions of any vagabond strolling by. The effigy is now propped up in a grim sort of fashion against the branches of a giant ivy. It is, perhaps, the most interesting relic in the abbey. It represents the doughty De Bigod in his chain-armor, with short sword and shield; and the probability is, it would have gone hard with his drunken assailant if the knight had been as much alive as the mariner took him to be.

Tintern Abbey has always en a favorite sojourning-ace with artists as well with poets. Wordsworth is a frequent visitor to the neighborhood, to which he is constantly returning in poems when prevented in returning in the flesh; and many other poets have de Tintern their theme. It is sufficiently remote from any railway station to avoid the common fate in our day certain abbeys more accessible to London, of being overrun by the excursionizing rabble; and even its striking beauty fails to lure it the cockney whose taste, time, and money are three somewhat limited. So the soft note of the soda-water bottle is not heard within its hoary walls, and the smell of the vulgar but convenient sandwich* pollutes not the purity of its hallowed atmosphere. To visit the well-preserved ruins of one such castle as Raglan is to realize in the plainest manner, and as can realized nowhere, perhaps, out of Wales, The very form and manner of the life led by the barons of mediaeval times. Ruined Raglan stands on a hill called by the Welsh Twyn y Ciros, by the English the Cherry Tump. Its outward walls were surrounded by an exterior moat, now filled up and overgrown with grass. Of the draw-bridge by which it was crossed there remains no sign, nor of the gate of entrance there. The second gate is the present entrance to the grounds. Two ivy-overgrown aqua towers stand sentinel at this great gate and a tree is growing on the top of one of them, behind the beautiful open-work parapet. The great stone bay-window which juts out into the court near by is probably one of the finest specimens of its kind to be seen any where in Wales. It is so massive in its proportions that the effect of its heavy stone frame-work is light and elegant, and with its rich festooning of ivy it is a beautiful picture. Opposite to this great window, within the banqueting hall it lighted, the baron’s table stood; over his head the arms of his house sculptured on the wall. The carved escutcheon is still plainly visible, though its motto is nearly obliterated, for the hall is roofless now and open to all weathers. A beautiful geometrical roof of |

|

10

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|