|

|

On The Welsh Border.,

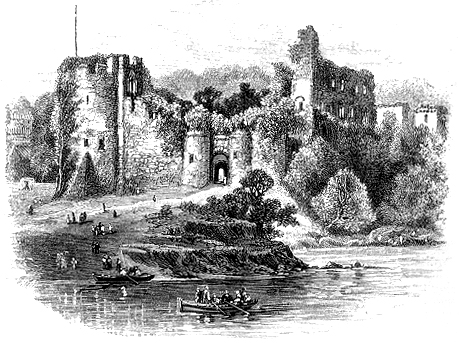

Page 3 of 14  Chepstow Castle, From The Bridge.

Older remains than those of Harold’s palace are discernible at Portskewitt — those of a Roman camp, on the top of the cliff looking on the Severn. It was erected here for the protection of the vessels lying in the river under it. On the very brink of this cliff is an old ruin called Sudbrook Chapel, very picturesque to see, and which will probably not be seen much longer, for the sandstone of the cliff is here very soft, and the water year by year washes it away. In the day when the chapel was built it stood far from the edge of the cliff; but the tooth of time gnaws never so greedily as when it moistens its repast with water, and the day must be near when the ruin will topple over into the Severn. The structure was originally the chapel of a Norman mansion whose stones were thus swallowed up as the river encroached on the land. Portskewitt is near to that crossing of the Severn which bears the name of the New Passage — a memorable point in the history of the Welsh border. In 1645 the unfortunate King Charles I. was pursued by his foes hither, and was ferried over the river, which is here two or three miles wide. Hot on his heels came Cromwell’s Puritans to the number of sixty, and forced the ferrymen to take them over too. The mariners complied sorely against their will, but instead of conveying the soldiers to the English shore, left them on a reef of rocks, called the “English Stones,” which stood high and dry, it being low tide. But before the soldiers could get from the rocks to the main-land, they were surrounded by the rising tide, the so-called river Severn being here really an estuary of the ocean, with a broad rocky beach, up and down which the tide creeps for many rods, at its ebb leaving dry land where at its flood rolls a deep sea. The soldiers were all drowned, and Cromwell abolished the ferry, which remained unused for nearly a hundred years thereafter. A large black rock which is seen here is asserted to be the precise spot where Julius Frontinus lauded with his Romans in the reign of Vespasian, on his expedition against the fierce Silures. Chepstow enjoys the special distinction, in a land where mere historical honors are easy, of sharing alone with Caerphilly in the poetic glory of "The Norman Horseshoe" Sir Walter Scott’s rendering of an ancient war-song of the men of Glamorgan, "Cadlef Gwyr Morganwg." "From Chepstow’s walls at dawn of morn

Was heard afar the bugle-horn, And forth in banded pomp and pride Stout Clare and fiery Nevill ride; They swore their banners broad should gleam In crimson light on Rhymney’s stream; They vowed Caerphilly’s sod should feel The Norman charger’s spurning heel. Chepstow’s brides may curse the toil That armed stout Clam for Cambrian broil; Their orphans long the art may rue That for Nevill’s war-horse forged the shoe." The Clares held Chepstow through several generations. The special Clare referred to in the song was that lord marcher who |

|

3

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|