|

|

Chapter III

Important Incidents of the Revolution

and Later History of Manhattan. New York Government at Sea—Plot to Assassinate Washington—Shocking Barbarity of English Officers—Hale and André, the Two Spies—Arnold in New York—British Evacuation—The Burr and Hamilty Tragedy of 1804—Robert Fulton and the “Clermont“—Public Improvements of 1825.

Arnold in New York, continued

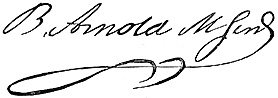

He would have been captured, and humanly speaking should have been, by Washington at West Point, had it not been for the unaccountable stupidity of Colonel Jameson, commander at North Castle, to whom André was given after his arrest. The papers found in his stockings, containing plans of all the West Point fortifications, a description of the works, the number of troops, the disposition of the corps, etc., etc., were all in Arnold's handwriting. These Jameson dispatched to Washington, but insisted on sending a letter stating these facts to Arnold, which apprised him of his danger and led to his hasty flight. The letter from Jameson was received by Arnold while at breakfast with his wife and several officers, He was greatly startled, but quieted the officers by stating that his presence was needed at the fortifications, and that he would soon return. His wife, with her infant child, had come from Philadelphia to join him at his post of duty but ten days previously. Summoning her to their private room, he informed her of his crime, and the necessity of his immediate flight. Overwhelmed with the announcement, she screamed, swooned, and fell upon the floor, and in this perilous condition he left her and fled for his life. Gaining the "Vulture," still anchored in the river, he proceeded to New York. Here he received his royal commission, and at length the stipulated price for his treason; but his crime was too naked and wanton to secure respect even from those for whom he had sacrificed his honor. He soon caused multitudes of patriots to be arrested and cast into dungeons, but in his precipitate flight from West Point he had left all his papers, and hence could produce no evidence against them. Covered with scorn, he lived in partial concealment, sometimes in the Verplanck House in Wall street, and again on Broadway, near the Kennedy House, Clinton's residence and headquarters. To save him from utter contempt when he rode out, English officers attended him, though it is said many of them thought it an ungracious task to appear at his side in the streets. While here, a plot was laid in the American camp for his capture, which nearly succeeded. The American troops were so stung with the disgrace he had brought upon their arms, that many were ready to enlist in any feasible enterprise to bring him to speedy retribution. Sergeant-major Champe, of the American dragoons in New Jersey, was the daring spirit of the band, who, by a connivance with his commanding officer, deserted the ranks and galloped toward the Hudson, but so hotly was he pursued by several troopers not in the secret that he plunged into the river and swam across to New York. His perilous, adventure gave the strongest evidence that his desertion to the British was genuine; hence, he was warmly received by all. He thus gained free access to Arnold's residence in Broadway, and adroitly matured a plan for his capture. His comrades were to cross from New Jersey in a boat opposite the house, under cover of darkness, pass up through an adjoining alley, enter the garden and gain access to the rear of the dwelling, seize and gag the victim, carrying him by the same route to the boat. Champe had loosened the pickets of the fence, the hour was appointed for the undertaking; but unfortunately, on the day previous to its execution, Champe's regiment was ordered to embark for Chesapeake, and Arnold removed his headquarters to another dwelling. Champe's comrades were punctual at the rendezvous, where they waited several hours for his appearance; and then returned in disappointment to camp. Not long after Champe made his escape from the southern army, and returned to his friends, to clear up the strange mystery that had hung over his conduct. Arnold left New York to command an expedition against Virginia, and afterwards led one against New London, Conn.; and is said to have watched with fiendish cruelty the burning of the town, almost in sight of the place of his birth. At the close of the war, he went to England, where he died unlamented, in 1801. It is said that he once expressed the sorrow that he was the only man living who could not find refuge in the American Republic.  Signature of Benedict Arnold |

|

40

:: Previous Page :: Next Page ::

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O’Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|