|

|

Life on Broadway, continued

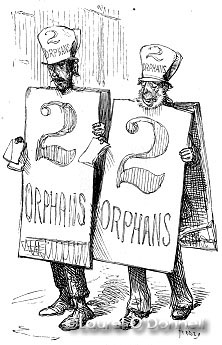

Right: Animated Sandwiches

manners; shrewd detectives with quiet, unobtrusive ways, altogether unsuspicious; telegraph boys in neat uniforms, carrying yellow envelopes that contain words penned ten minutes previously in California; railway magnates more important than many kings; spruce clerks and laborious porters — are included in the throng which passes

before us in an almost solid body.

All is not toil and trouble with the merchants, however. Across the way is the white marble façade of a celebrated restaurant, where, after a successful stroke of business, a lucky handling of wheat or Erie, the masters of the situation make merry over the costly vintages of Champagne and Burgundy, sometimes prolonging their revels to an hour when all the adjacent streets are dark and vacant, and Trinity spire points solemnly to the deep blue night sky. Soon after six o'clock the high pressure of the traffic down town abates, the offices are closed, a single lamp being left burning in each to reveal the interiors to the policeman, and the tired-out workers seek their homes. By nine o'clock the street is quiet. A few pedestrians pass to and from the Brooklyn ferries at Whitehall. Between midnight and four o'clock the telegraph and newspaper offices send out their wearied operatives. The street is never quite empty, but the rapid change that takes place at night-fall, previous to which every stone and flag has seemed to have a voice, suggests a visitation of palsy. A short distance north of Trinity, Park Row slants off from Broadway, being separated from the latter thoroughfare by the new Post-office and City Hall Park. Lights are burning over there all night. Men smirched with ink and pale with toil are coming and going constantly. Those high buildings are the offices of the great morning newspapers — the Herald, the Times, the Tribune, the Sun, and the World. The upper stories, in which the editorial and composing rooms are situated, blaze with light, and on the ground-floor a paler beam shows the advertising-rooms, where a few sleepy clerks await the last advertisements. The imagination can not encompass the nervous reach and power of the influence which those steadily burning lamps symbolize. Sitting under the trees of the Park, which is an agreeable break in the high-walled street, we are passed from time to time by reporters hurrying to their offices with rolls of "copy" bearing on every current topic — lectures on evolution, sermons, theatres, fires, murders, receptions, funerals, and weddings. An hour or so later the same slaves of the lamp pass us again as they go home; later the editorial writers are seen, and later still the proofreaders and compositors. The editor-in-chief drives home in a coupé. The lawgivers and law-makers — people in themselves mighty, but not as mighty as he — have waited upon him in humility, and accepted a moment's audience as a boon. He is the incomparable planet of American civilization, although the lustre of the satellites sometimes outshines the planet itself, and as he composes himself in the corner of his modest carriage, his brain reflects in epitome the history of the world for a day. On a calm evening we can hear the roar of the presses on our bench in the Park, and in that roar we fancy that we can make out the articulation of the power which the myriad white sheets are to have in the morning. While the lower part of Broadway is filled during the day with urgent business men and is deserted at night, the upper part is chosen for purchases and promenade by a much more brilliant throng, and is busy both night day and day. About two miles from the foot of the street the northward-bound traveller finds himself emerging from the close quarters of the street into one of those verdurous squares which lend a great charm to the city. In the mornings and afternoons the benches and the asphalt walks of this bit of country in town are crowded with white-capped nurse-maids attending prettily dressed children; more or less disagreeable idlers, varying in distinction from the tramp to the slightly overcome tippler; and the pedestrians, who are glad enough to vary the monotony of the flag-stone sidewalk with a glimpse of the smooth grass-plats and the |

|

Page 6

Books & articles appearing here are modified adaptations

from a private collection of vintage books & magazines. Reproduction of these pages is prohibited without written permission. © Laurel O'Donnell, 1996-2006.

|

|